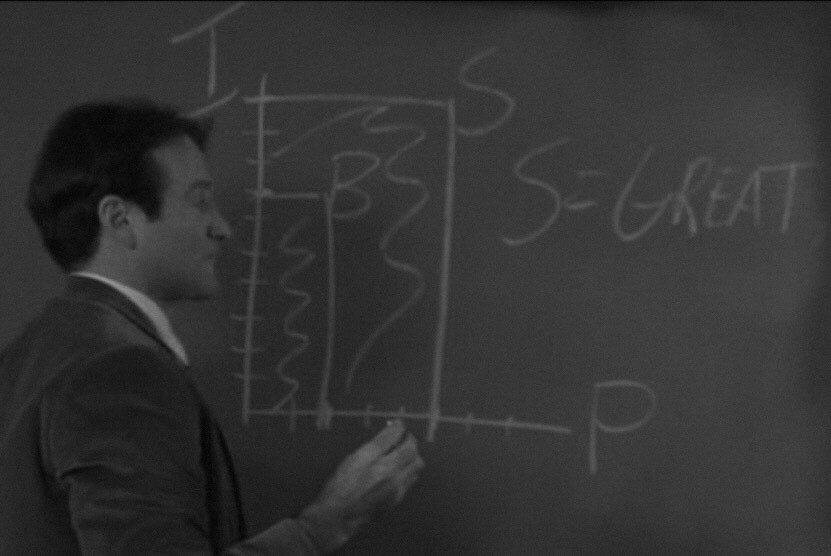

Early in the film DEAD POETS SOCIETY (1989), English teacher John Keating, played by Robin Williams, gives a scathing critique of a framework that calls for evaluating the relative “greatness” of poetry by asking readers to consider things like the poem’s rhyme and meter then judge how well it “performs” in such areas.

We’re talking about poetry. How can you describe poetry like American Bandstand? “I like Byron, I give him a 42 but I can’t dance to it.”

Mr. Keating calls on his students (and on us as audience) to focus more on how poetry, as well as other forms of art and literature, impacts or, literally, moves us than on how we might dispassionately evaluate it in some ostensibly objective way.

This brings us to a point I raised in an earlier post on how comments in online audience film reviews tend to focus more on evaluations of “performance” (e.g., in acting and plot pacing) than on experiences of the film’s impact.

This issue of how we’re asking for audience feedback was the topic of a recent article about film test screenings (Sharf, 2020). The filmmakers discussing their own experiences attending test screenings noted how what they observed and felt from audience reactions during the screenings often differed from audience responses on questionnaires and in focus groups following the screenings.

I believe the difference is due to the questions asked.

Before getting to the types of questions asked in film test screenings, I want to quickly review a key observation I’ve had in conducting human insights research over the past 20 years. Starting with my dissertation about spiritual identity development, I noted how study participants tended to describe spiritual beliefs (e.g., about the existence of God) without necessarily being able to come up with specific reasons for having those beliefs. They just knew. If pressed, they might come up with reasons, but it wasn’t often clear to me, or to them, that those reasons were the actual driving factors behind their beliefs. I concluded that spiritual development, at least for participants in my study, was largely an intuitive/experiential process rather than a predominantly rational one, a conclusion which differed from most theory in that domain at the time.

When I checked my surprising, at least to me, findings against published studies to see if others had observed similar intuitive processes, I found what was then a new, compelling study which asserted moral action is primarily driven intuitively rather than rationally (Haidt, 2001), which also differed from prevailing ideas at the time. While individuals can supply, if pressed, rational reasons for their moral actions, those reasons aren’t often the real reasons, which tend to me more feeling-based.

In reviewing example film test screening questionnaires (see Galloway, 2006; How am I doing?! The independent filmmakers’s guide to feedback screenings, 2010), questions asked typically include items like the following:

- “What was your reaction to the movie overall?” [response scale: excellent, very good, good, fair, poor]

- “How would you rate each of the following elements of the movie?” , e.g., “The pace”, “The character development”, “The cinematography/visuals” [response scale: excellent, very good, good, fair, poor]

- “What do you think the film was trying to say?”

Questions like these take viewers out of their own experience of the film and ask them to rationally rate, and dissect, the individual elements. Even with the first question that ostensibly asks about viewers’ “reaction” (i.e., their particular experience, the film’s impact on them personally), the response scale calls for them to step away from their own experience to give the film a grade, just like the poetry evaluation framework in DEAD POETS SOCIETY!

One of the common things I need to do in research interviews and, especially in focus groups, is keep participants grounded in their own experiences. In wanting to be helpful, participants often try to think what others not being interviewed might think or what, rationally, might be things that could be done to improve experiences and impact (e.g., from a health care intervention) even though such things aren’t necessarily relevant to their own experiences and impact. I have to bring them back to the questions that ask about their own experience, which do not appear to be emphasized in film testing screening questionnaires.

I’ll propose a set of such alternate experience-grounded test screening questions in my next post.

References

Galloway, S. (2006, July). Test screenings. Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved from https://www.hollywoodreporter.com

Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: a social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4), 814-834.

How am I doing?! The independent filmmaker’s guide to feedback screenings (2010, December). Retrieved September 5, 2020 from, http://nobudgetfilmschool.com

Sharf, Z. (2020, August). Roger Deakins and ‘Blade Runner 2049’ Editor Debate Test Screenings: ‘Weapon’ or Savior? Retrieved September 5, 2020 from, https://www.indiewire.com

Joud AlAmri

September 5, 2020 9:41 pmThis was a great read and I absolutely believe that when we look to art and literature we should first look to whether it moved us or not then we can move on to any sort of critical analysis of it. I think we get too bogged down by technicalities and what should and shouldn’t be done that we lose sight of the personal experiences it can offer us.

Justin B Poll

September 6, 2020 3:40 amThank you, Joud!