Understanding the Early Success of Sherwood Pictures

NOTE: I’m breaking from my originally planned post about how research can help us develop impactful films to respond to a request by Leticia Greenwood of Seni Studios about a paper I wrote last year on this successful producer of Christian films. The importance of insights into core human needs (developed through research!) is highlighted in this paper, so in a way, it’s a great intro to what I was planning to post anyway. Win-Win!

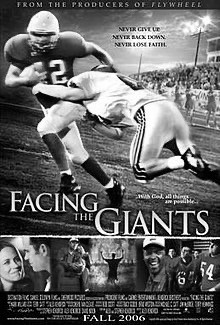

Buried within a subpage of the movie financial data tracking website The Numbers is a table entitled “Most Profitable Movies Based on Return on Investment” (Movie Budget and Financial Performance Records, n.d.). The table lists twenty films, sorted by highest rate of return (e.g., box office revenue, video sales) from investment (e.g., projected production and marketing costs): five horror films such as 2009’s PARANORMAL ACTIVITY (#2) and 2010’s PARANORMAL ACTIVITY 2 (#14) along with relatively recent breakout hits like 2006’s HIGH SCHOOL MUSICAL (#12) and breakout hits from farther back such as 1977’s STAR WARS (#11) and 1946’s IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE (#15). Situated at #1 and #3 on the list are two independent Christian films, 2006’s FACING THE GIANTS and 2008’s FIREPROOF respectively, both produced by the same company: Sherwood Pictures.

Sherwood Pictures is defined as a “ministry” of Sherwood Baptist Church in Albany, Georgia (Sherwood Pictures, n.d.). Under the direction of Michael Catt, Senior Pastor of the church, and driven by then amateur filmmaker brothers Alex and Stephen Kendrick, the group decided to get involved in Christian independent filmmaking as a means to impact the larger culture for good and to “communicate the gospel (of Jesus Christ) without compromise” (Catt, n.d.).

The initial films produced by Sherwood were FLYWHEEL (2003) and the aforementioned FACING THE GIANTS (2006) and FIREPROOF (2008). Collectively, these three films cost less than $1 million to make (a projected $620,000) and have grossed an estimated $145 million (Facing the Giants (2006), n.d.; Fireproof (2008), n.d.; Flywheel (2003), n.d.).

The purpose of this paper is to explore four possible factors that might explain the initial financial success and, possibly, “ministry” impact success of Sherwood Pictures and to propose possible ideas for increasing such success in both areas (financial and impact) moving forward.

Based on my review of the three films, the reviews by others of the films and of the production and marketing efforts around the films, and other relevant concepts, I believe the initial success of Sherwood Pictures may be attributable to: (1) identifying a specific Evangelical Christian audience niche that may have been under-served by (if not at odds with) the larger Hollywood film industry, (2) keeping costs of production very low but building increased capacity with each successive film, (3) tailoring marketing and distribution strategies to the identified audience niche in partnership with an established Hollywood player, and (4) addressing core psychological and spiritual needs of their target audience in the stories they tell.

Identifying an under-served niche

“For us, most of what is coming out of Hollywood does not reflect our faith and values.” These comments made by Alex Kendrick (Bloom, 2008), who directed all three of the films, co-wrote all three, and acted in the lead role in the first two, suggests a previously under-served audience niche for their films: Evangelical Christians.

Others (Russell, 2010) have likewise suggested a disconnect between the Hollywood establishment and this religious segment of the population, both in terms of what films contain (e.g., actions and themes at odds with some religious moral sentiments) and what they don’t (e.g., positive portrayals of religious actions and themes).

In my own viewing of the films, I observed no swearing, nudity/suggestive sexuality, or violence to speak of (beyond isolated scenes of lashing out in anger by main characters in FLYWHEEL and FIREPROOF), while there were several instances of prayer, Bible reading, and references to Jesus as a means of successfully dealing with life difficulties. Beyond simply serving the niche, it has been suggested by others (Russell, 2010) that Sherwood emphasizes their separateness from the Hollywood establishment to solidify the niche even though they have ongoing ties to that establishment though their marketing and distribution relationship with Sony-affiliated Provident Films.

The production of films with characters that Evangelical Christians can relate to and who are trying to live according to similar morals and to pursue things they also value (e.g., strengthening marriages, honoring God) even though (and even because) the characters struggle to do so makes it more likely, according to some research, that members of the target population will engage with such films and feel positively impacted by having seen them (Eden, Daalmans, & Johnson, 2017; Konijn & Hoorn, 2005).

Keeping production costs low

While perhaps axiomatic, the fact that Sherwood has kept production costs low across their first three films, despite considerable financial success by at least the second film, makes it easier for them to achieve favorable rates of return on financial investment. Projected production costs were $20,000 for FLYWHEEL, $100,000 for FACING THE GIANTS, and $500,000 for FIREPROOF (Facing the Giants (2006), n.d.; Fireproof (2008), n.d.; Flywheel (2003), n.d.). Such low costs were achieved by engaging largely volunteer casts, production teams, and post-production teams, with most of such volunteers being drawn from the Sherwood Baptist Church’s own congregants (Bloom, 2008).

While not directly referenced by other reviewers, the impressive cost-efficiency of their productions might also be explained by keeping several of the same actors and likely many of the same people behind the scenes across all three films, which could reduce the time and effort needed to build team cohesion while also increasing the individual and collective capacity of team members. Others (Bond, 2011) have observed improvements in the movie-making skill and execution with each successive Sherwood film, something I personally noted through my viewing of the films in the order they were produced.

Tailoring marketing and distribution strategies

Most of the other reviewers I identified who formulated explanations as to the financial success of Sherwood highlight the group’s efforts in reaching out to targeted key influencers in the Evangelical Christian community, such as pastors, through private screenings and other events (Bloom, 2008; Debruge, 2007; Russell, 2010). The funding and insights that made such outreach efforts so successful may be attributable more to their partner Provident Films (Russell, 2010).

Again, while not directly referenced by other reviewers, the effective audience-building and audience-rallying efforts of Sherwood and Provident Films may be attributable to keeping largely the same teams intact across all three films (or, at least, the second and third film). Not only would this increase the capacities of the individual members and teams but would also enable building upon the grassroots connections previously established with each new film, especially as the type of film and the intended audience remain largely the same. Others (Bond, 2011) have observed such improvements in the marketing tactics used to promote each successive Sherwood film.

Addressing core psychological & spiritual needs

Finally, a factor I believe may be key to the early success of Sherwood, and one that seems largely overlooked, if not trivialized, by other reviewers of the company and of the films themselves, is the focus on addressing core psychological and spiritual needs that many within (and likely outside of) the target Evangelical Christian population share and where they might often struggle.

Regarding such needs, others (Exline, 2002) have suggested Christian believers may struggle in core universal need areas (Ryan & Deci, 2000) shared also by non-believers such as feeling disconnected in their personal relationships and feeling they are failing to be as strong or competent as they need to be, while they may also have struggles in need areas more foreign to non-believers such as having angry feelings toward God (a special kind of relationship) and losing faith in God (a special kind of competence).

Reviewers of the early Sherwood films seem to miss or dismiss the magnitude of what the main characters are going through. Russell (2010), for example, suggested, “Like Sherwood’s other films, Fireproof focused on the fairly pedestrian travails of small-town, working class southerners.” Bond (2011) seems to identify some struggles in the films’ main characters, “With Fireproof…it was men seeking help to become better husbands, and with Giants and Flywheel, it was men seeking to help in their professional lives,” while missing key others. Leland (2006) not only misses key depicted needs and struggles but also seems to shallowly touch on those identified in comments like, “Grant (lead character in FACING THE GIANTS) announces he’s dedicating himself to Christ and redirecting his players to ‘honor God’ by playing better.”

From my own viewing of the films, I saw depictions of struggles with universal human and uniquely Christian needs greater in scope, depth, and meaning than seem represented in other reviews. In all three of the films, the main characters struggle with feelings of failure or inadequacy, not only in their “professional lives” but also fundamentally as people and believers. In two of the three films the main characters struggle desperately with the prospect of failed relationships with spouses and children, not just trying to be “better husbands”. In all three of the films, the main characters struggle either with their feelings toward God, their strength of faith in God, or both, which prompts characters like Grant to seek better ways of connecting his life to God and “honoring God” in all aspects of his life: in his relationship with his wife, in his job as a high school coach, not just as a means of getting his football team to “play better”.

Summary of success factors

In sum, the early success of Sherwood Pictures, which is considerable, may be attributable to the combined forces of four primary factors including identifying an under-served audience, keeping production costs low, tailoring marketing strategies to the identified audience, and creating stories that address core psychological and spiritual needs of their audience.

Moving forward

“What’s the purpose of this team?”

This question posed in FACING THE GIANTS may also be applied to Sherwood Pictures. Considering clear goals for one’s films has been suggested by others as a key step that should inform every aspect of the process: from development, to production, to marketing and distribution (Reiss, 2009). While it’s clear from my review that leaders of Sherwood have considered such goals, their goal to positively impact the larger culture (including, ostensibly, those outside of their faith) might be at odds with their goal to communicate or “preach” tenets of their Evangelical Christian faith “without compromise” (Catt, n.d.).

As I suggested above, a strength of the early Sherwood films, from my viewings, seems to be they address core, and common, human struggles, shared by Evangelical believers and non-believers alike, and they offer at least some possible solutions to those struggles (e.g., finding a secure base for one’s life in the teachings of Jesus to help with fears of failure), but the seeming exclusivity of the solutions presented as the only way to fulfill needs and the forcefulness with which the solutions are presented may limit their appeal to, and positive impact on, non-believer would-be audience members (Russell, 2010) and even believer would-be audience members (Exline, 2002). This might be especially true if such audience members don’t experience the same sort of “happily-ever-aftering” (Leydon, 2008) and “unbroken string of triumphs” (Leydon, 2006) portrayed in the lives of Sherwood’s main characters after implementing those solutions.

If they want to increase the reach of their “ministry” to impact more lives for good (and perhaps also increase the amount of financial return, not just the rate of return), Sherwood might do well to insert their Christian practices (e.g., prayer) and principles (e.g., belief in a Higher Power) in their films though more inclusive and careful (but not necessarily “compromising”) ways like have been done with other high ROI films, IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE with prayer and STAR WARS with belief in Higher Power, with reaches vastly exceeding those of Sherwood’s films.

References

Bloom, J. (2008, October 5). It’s a healthy marriage of faith and filmmaking. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com

Bond, P. (2011, October). Box office shocker: how moviemaking Georgia church behind “Courageous” outperforms Hollywood. Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved from https://hollywoodreporter.com

Catt, M. (n.d.). Our Beginning. Retrieved February 5, 2019 from, http://sherwoodpictures.com/how-we-do-it/

Debruge, P. (2007, April). The gospel according to research: Hollywood courting faith community. Variety. Retrieved from https://variety.com

Eden, A., Daalmans, S., & Johnson, B.K. (2017). Morality predicts enjoyment but not appreciation of morally ambiguous characters. Media Psychology, 20:349-373.

Exline, J.J. (2002). Stumbling blocks on the religious road. Psychological Inquiry, 13(3):182-189.

Facing the Giants (2006). (n.d.) Retrieved February 5, 2019 from, https://www.the-numbers.com/movie/Facing-the-Giants#tab=summary

Fireproof (2008). (n.d.) Retrieved February 5, 2019 from, https://www.the-numbers.com/movie/Fireproof#tab=summary

Flywheel (2003). (n.d.) Retrieved February 5, 2019 from, https://www.the-numbers.com/movie/Flywheel#tab=summary

Konijn, E.A., & Hoorn, J.F. (2005). Some like it bad: Testing a model for perceiving and experiencing fictional characters. Media Psychology, 7:107-144.

Leydon, J. (2006, October). Facing the Giants. Variety. Retrieved from https://variety.com

Leydon, J. (2008, September). Fireproof. Variety. Retrieved from https://variety.com

Movie Budget and Financial Performance Records. (n.d.). Retrieved February 5, 2019 from, https://www.the-numbers.com/movie/budgets

Reiss, J. (2009). Think outside the box office: The ultimate guide to film distribution and marketing for the digital era. Hybrid Cinema

Russell, J. (2010). Evangelical audiences and “Hollywood” film: Promoting Fireproof (2008). Journal of American Studies, 44(2):391-407.

Ryan, R.M., & Deci, E.L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1):68-78.

Sherwood Pictures. (n.d.). Retrieved February 5, 2019 from, http://sherwoodpictures.com/

Leticia Greenwood

July 31, 2020 12:24 amHi Justin,

You succinctly summarized Sherwood Pictures success: filling a void for the Evangelical Christian, low cost production, targeted marketing & distribution, and meeting the needs of the target audience both spiritually and psychologically.

As you mentioned in your post, several of Sherwood’s early films delved into the human struggles of the Christian: doubts, fears, temptation, relationships, marriage, and parenting. As a Christian, I can appreciate and relate to those particular struggles myself. I love how each of their films points the audience member to the gospel of Jesus Christ.

However, the quality of production, and acting in Sherwood Pictures films (along with other Christian films) can be improved. I believe we’re image-bearers of Christ. Therefore, our creativity should reflect the ultimate storyteller: Jesus. I have a lot to say on the subject, but as I mentioned in my blog, I’ll save it for another time.

In regards to Sherwood Pictures reaching a wider audience, I would have to agree with you. With out compromising their beliefs, the studio would have a “far-reaching net” in reaching a world-wide audience with more inclusive stories that touch on Christian principles.

Justin B Poll

August 1, 2020 8:01 pmThank you, Leticia, for your comments.

I agree there may be significant flaws in production and acting in some Christian films that, if addressed, could increase their appeal and impact. I certainly don’t claim to be an expert in either of those domains (acting or producing). I have found for me personally I can largely “forgive” such flaws if there is genuine heart/insight in a film.

One such example for me is a Christian/religious film called SATURDAY’S WARRIOR (1989, remake in 2016). While even I recognize some limitations in its production value (e.g., perhaps cheesy songs and dialogue), the “soul” it contains (e.g., insights about where one can find meaning outside oneself and healthy identity), in my opinion, shines through those things and still engages and impacts me for the better.

Ideally all elements would be at play, both good style and good substance/soul; I just tend to notice lack in the latter more than in the former.